You decided it was finally time to do a marathon—not the 26.2 mile run—the Netflix sort.

Before your next episode can load, you peel yourself off the couch and hobble your way to the stairs.

Your body feels stiff. You shrug it off.

By the time you reach the top of the stairs, your breathing is heavy. You shrug it off.

You mindlessly wander around the kitchen looking for something to eat but can’t think clearly. There’s a million distractions, to-do’s, and worries swirling through your head.

All the mental chatter and rumination makes you feel anxious.

All you want to do is escape the crappy feelings, so you reach for a quick fix: more Netflix, ice cream, booze, etc., and plop yourself back down on the couch.

It’s not that Netflix or ice cream are the enemy. (I’m a Netflix fan myself!) It’s that too many sedentary activities on your couch only reinforce escapism and procrastination. They might distract you for a moment, but they do little to build you a resilient body and brain.

There is one thing that will reshape your nervous system and help you cope with all of life’s hardships — Exercise.

Exercise not only produces immediate changes in your physiology that boost your mood, it actually rewires your nervous system to become more flexible, energized, and resilient.

The Magic of Movement For Your Mood

If you’re in a bad mood, go for a walk.

Still in a bad mood?

Go for another walk.

Tongue-in-cheek, perhaps. But the truth is that moving your body, especially outside, can benefit your mood in numerous ways.

The combination of fresh air, a change in temperature, and natural light can help reset your circadian rhythms. Getting your body in sync with nature can alleviate some of the detrimental effects of artificial lighting, endless screen time, and our modern built environment.

But if you truly want to let go of nagging narratives, buffer your anxiety, and build a better brain, moderate or intense exercise is the best medicine for the mind.

When you understand the links between physical fitness and the brain, you can see how exercise produces short, medium, and long-term shifts in your physiology and psychology that help you live at your best.

Physical Fitness And The Brain: Getting Into Flow

Maybe you’ve experienced that wonderful feeling of “getting out of your head” and back into your body. It’s one of the most common reasons people enjoy working out—it turns off that incessant neurotic voice in your head.

In fact, shifting your attention away from the burden of daily tasks may be one of the few reasons that exercise actually makes sense in our modern world. Because, let’s face it, in the affluence of modern society, there is no fundamental reason to push your body hard.

In the past, strenuous physical movement was simply a part of daily survival. Since that is no longer the case, exercise will always be an add-on to daily living.

As a result, if you want to be engaged with exercise, you need to develop a taste for it. You need to see it, not as a burden, but for what it can give you: A healthier body and a better brain.

The clear-headedness you experience from working out may be more than just a rush of endorphins. It may be a product of your brain’s finite resources trying to manage the physical demands of exercise.

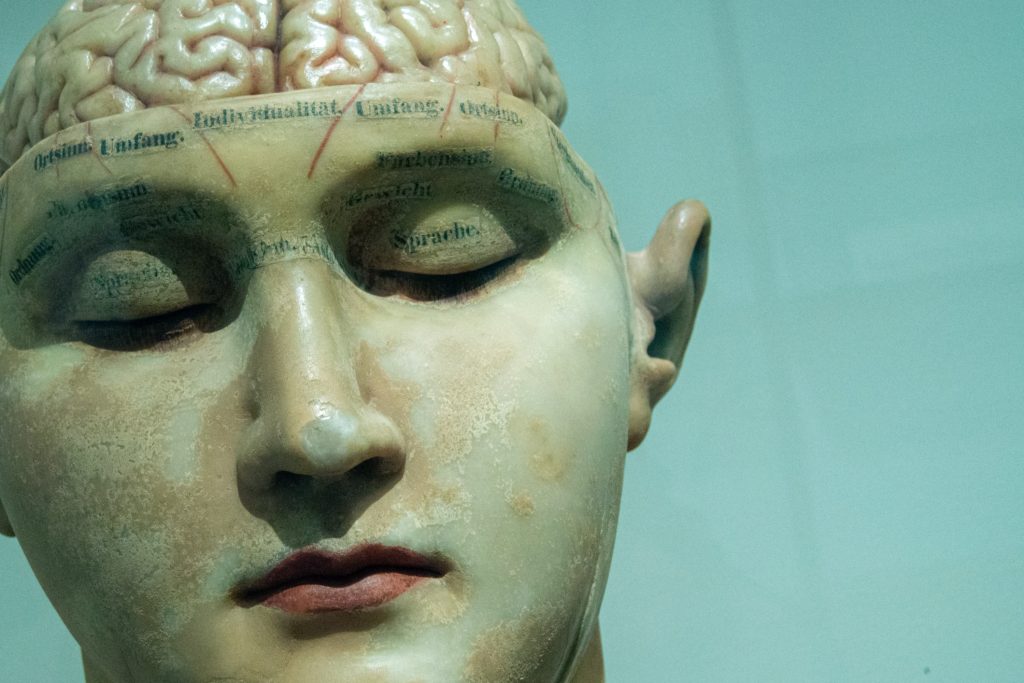

Researchers call it the “Exercise-Induced Transient Hypofrontality Hypothesis.”

In other words, exercise forces your brain to redistribute resources to what matters most in the moment, namely keeping your body alive while in motion.

When you’re lifting heavy weights over your head, running down a mountain, or preforming complex movement patterns, your nagging thoughts about what’s for dinner are not pertinent to survival.

Your nervous system doesn’t care about replaying that annoying email from your boss over and over in your head. It has more important things to attend to.

As a result, your brain shifts from an overactive “monkey mind” to a present-focused attentiveness. In turn, a lot of your obsessive thoughts fade away.

In the paper, “Functional Neuroanatomy of Altered States of Consciousness: The Transient Hypofrontality Hypothesis,” Arne Dietrich explains this shift in the brain during exercise:

Excessive activity [of the prefrontal cortex] generates a state of hyper-vigilance and hyper-awareness. In such a state, there is a tendency to overanalyze and evaluate every event with respect to personal relevance. Exercise might simply take the edge off by neutralizing this circuitry, producing an inability to focus on life’s worries.

An inability to focus on life’s worries seems nice, doesn’t it? To be fair, this hypothesis remains to be proven. (It’s hard to get good brain data when people are running around.) A general mechanism of transient hypofrontality may be overly simplistic from a neurocognitive point of view.

Regardless of the exact mechanism by which it occurs, there is no refuting that exercise can reliably alter your consciousness and help you experience what is often referred to as ‘Flow’: a relaxed yet fully engaged experience where time and thoughts fade away and you become engrossed in the moment.

Unfortunately your couch isn’t good at facilitating flow. Nor are most passive and sedentary activities.

Without some movement, deep embodiment, and immersive challenge, your attention tends to drift inward and get caught in loops of repetitive, obsessive, and negative thoughts. If you want to do something about this rumination, exercise is the best place to start.

Exercise Releases Endorphins & Endocannabinoids

The most interesting research on exercise as an antidepressant looks at ways your body activates innate opioid and cannabis systems to reduce pain and boost your mood.

You may be familiar with the popular idea that exercise can cause an endorphin-based high. The idea is that that prolonged rhythmic contractions of skeletal muscle (e.g. running) can release endorphins. These are compounds that activate the body’s opiate receptors, causing an analgesic effect. Together with other neurotransmitter systems, these chemicals can blunt paint and produce euphoria that lasts for hours after your workout.

In a similar vein, your body can produce analogs of the same substance you get from smoking cannabis. This endocannabinoid system is found to impact all sorts of bodily functions from immunity to diminishing anxious behavior.

During exercise, your body releases endocannabinoids such as anandamide, AEA, and 2-AG that regulate your HPA axis response to stress. They not only influence your mood by altering pain perception and elevating emotions, but they also instruct your body to produce fewer stress-hormones in response to non-threatening stimuli.

From a purely physiological perspective, exercise has the potential to release a powerful cocktail of chemicals that is not far from taking opiates or smoking a joint. Of course without all the negative side-effects and potential for abuse.

Physical Fitness Rewires Arousal Networks In The Brain

Exercise is a stressor, but used strategically, it can help calm arousal networks that might otherwise produce an overly anxious state. First, you must understand that the body responds to increased stress by flooding your system with hormones like cortisol and norepinephrine. This stress can be physical, like exercise or real danger, or purely mental, as in all your worries and woes.

In the short-term, these hormones help mobilize energy and resources so your body is ready for action. In the long-term, elevated levels of stress hormones like cortisol can lead to weight gain, anxiety, and mood issues.

For exercise to maximally benefit your body and your mood, you need elevate stress hormones acutely but not chronically. This means you need to push it hard and then recover like a champ.

Without proper recovery, you’re likely to add stress onto an already stressed system. When it comes to physical fitness and the brain, over-exercising or not enough recovery can be a disaster for your mood. It creates chronic low-level activation of your sympathetic nervous systems that dampens your resilience and drains your resources.

With the help of a coach or fitness professional, you can use exercise as a smart tool to enhance the flexibility of your nervous system. A smart exercise routine with adequate recovery can rewire your arousal networks and increase your body’s tolerance to stress, so you’re better able to move from fight-or-flight or rest-an-recover without getting stuck in one or the other.

From a fitness perspective, this is the adaptation you’re looking for. A greater tolerance for stress means you can push harder, run faster, and return to baseline quicker. What used to throw you into overexertion will no longer redline you.

When looking at physical fitness and the brain, rewiring your arousal networks can have a tremendous benefit on your mood.

The mood-boosting and anti-anxiety effects of exercise seem to be largely mediated by the production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is like fertilizer your 100 billion brain cells. It enhances neuroplasticity, allowing new neurons to grow and connect.

BDNF acts as an anti-depressant by up-regulating different types of neurotransmitters like serotonin neurons and GABA. Together these can lift your mood and calm your down. Studies in rats found that regular exercise (typically aerobic exercise above 70% of your max heart rate) promoted the development and rewiring of neurons that may calm excitatory circuitry in the hippocampus.

In other words, exercise produces BDNF that changes neuron growth and connectivity in areas of the brain that regulate stress and anxiety. In fact, BDNF may have synergistic effects with endocannabinoids to further increase your neuroplasticity brain’s ability to rewire itself for greater resilience.

Start With “Movement Snacks” For Your Brain

Exercise is not an answer to a shitty lifestyle. But there’s no question physical activity improves brain health by promoting the development of new neurons. Regular exercise reprograms your nervous system to better handle stressors and can feel wonderful when all those “happy” neurohormones kick-in.

The catch is that it can be hard to motivate yourself to do something energetically demanding, especially when you’re feeling low. Sitting on the couch and watching Netflix often seem like more appealing options.

If only you think of exercise as a chore or a burden, you’ll never want to do it. But if you think of physical fitness as an opportunity to build a better brain and develop your resilience, you can reframe exercise as a tool for your mental health.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to exercise. You need to assess where your mindset and body are currently and start building slowly from there.

For some, this may mean re-upping your old workout routine. Adding in new types of movements or adjusting the intensity so you’re optimizing your hormones and recovery may enable you to gain even more benefits to your body and brain.

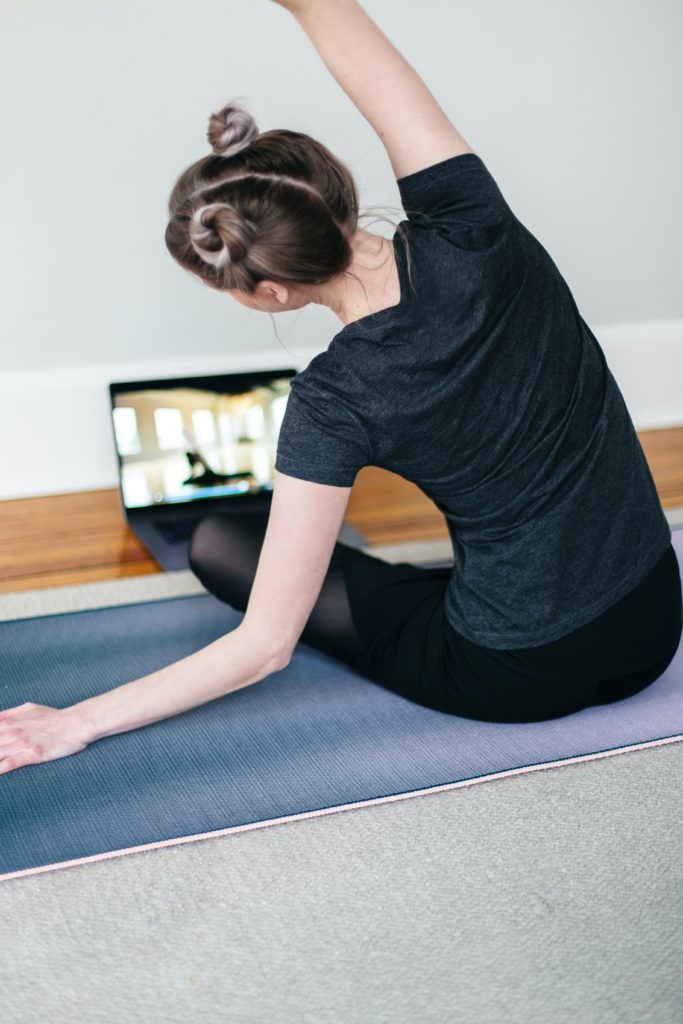

If you’re just getting started, it may be best to break-down exercise into bite-sized “Movement Snacks” throughout the day. This is a simple ~10min burst of exercise sprinkled into your schedule. For example, you could:

- Shift your working position regularly. Alternate between sitting, standing, and kneeling. If you can, walk and talk.

- Get an exercise ball and a yoga mat so you have options to bounce and stretch during the day.

- Run up and down a few flights of stairs. Drop and do some push-ups. Flow through some yoga or just walk around the block.

- Try a workout video or app like the scientific 7-min workout. Schedule it into your day between appointments, meetings, or events.

- Have a dance session. Load up 3 of your favorite songs and boogie down. Try staying in motion and exploring different ways of moving your body.

There are lots of creative ways to get moving. Although movement snacks aren’t a total replacement for longer duration and higher intensity exercise, they are the foundation for a holistically healthy life.

Moreover, movement snacking is pragmatic, and that’s essential because every day little choices affect your physical fitness more than you can imagine.

Any sustainable lifestyle change begins with awareness. When it comes to physical fitness and the brain, becoming aware of how a sedentary lifestyle is robbing you of the chance to upgrade your brain may make you think twice about that next marathon (Netflix, that is!)

~ Jeff Siegel

Download your free Healthy Habits Checklist & Workbook.

If you’d like to explore working together, you can schedule a private 20-min consultation call with me.

References:

Del Giorno, J. M., Hall, E. E., O’Leary, K. C., Bixby, W. R., & Miller, P. C. (2010). Cognitive function during acute exercise: a test of the transient hypofrontality theory. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 32(3), 312-323.

Dietrich, A. (2003). Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: The transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Consciousness and cognition, 12(2), 231-256.

Dietrich, A. (2006). Transient hypofrontality as a mechanism for the psychological effects of exercise. Psychiatry research, 145(1), 79-83.

Dietrich, A., & Audiffren, M. (2011). The reticular-activating hypofrontality (RAH) model of acute exercise. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(6), 1305-1325.

Stoll, O., & Pithan, J. M. (2016). Running and Flow: Does Controlled Running Lead to Flow-States? Testing the Transient Hypofontality Theory. In Flow Experience (pp. 65-75). Springer, Cham.

Wang, C. C., Chu, C. H., Chu, I. H., Chan, K. H., & Chang, Y. K. (2013). Executive function during acute exercise: the role of exercise intensity. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(4), 358-367.

Dietrich, A., & Al-Shawaf, L. (2018). The transient hypofrontality theory of altered states of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 25(11-12), 226-247.